THE HISTORY OF KINGMAN + HERITAGE ISLANDS

Kingman Island (also known as Burnham Barrier) and Heritage Island are islands in Northeast and Southeast Washington, D.C., in the Anacostia River. Both islands are man-made, built from material dredged from the Anacostia River and completed in the early part of the 20th Century. Kingman Island, Kingman Lake and nearby Kingman Park are named after Brigadier General Dan Christie Kingman, the US Army’s Chief of Engineers who died in 1916 while the project was underway.

Kingman Island is bordered on the east by the main channel of the Anacostia River, and on the west by the 110-acre Kingman Lake, which is a side channel of the Anacostia. Heritage Island is surrounded by Kingman Lake. Both islands were federally owned property managed by the National Park Service until 1996. They are currently owned by the District of Columbia Government and managed by Living Classrooms of the National Capital Region. Kingman Island is bisected by Benning Road and the Ethel Kennedy Bridge, with the southern half of the island bisected again by East Capitol Street and the Whitney Young Memorial Bridge. Part of Langston Golf Course is located on Kingman Island north of Benning Road, while the southern half of Kingman Island and all of Heritage Island are largely undeveloped.

Early History

Prior to the arrival of European settlers in the late 17th century, the Anacostia River was a relatively deep tidal river flanked by extensive wetlands. Seagoing ships could sail up the Anacostia as far as Bladensburg, MD, a commercial seaport established in 1742, several years before Alexandria and Georgetown and 58 years before the District of Columbia.

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, as landowners cleared much of the surrounding forest for farmland, unchecked soil erosion carried by Anacostia’s network of tributaries filled up the river and large mudflats ("the Anacostia flats") formed on both banks of the Anacostia River. The last sailing ship reached Bladensburg in 1840. By 1876, a large mudflat had formed immediately south of Benning Bridge and another flat some 740 feet (230 m) wide had developed south of that. By 1883, a stream named "Succabel's Gut" traversed the upper flat and another dubbed "Turtle Gut" the lower, and almost all flats on the river hosted substantial populations of American Lotus, lily pads, and wild rice.

Early sewage systems poured untreated animal and human waste into the Anacostia. The waste accumulated on the mud flats, creating a prime breeding ground for disease-carrying mosquitoes and other insects. In 1895, the US Surgeon General reported that 98% percent of Navy Yard workers had suffered from malaria during the year. Civic associations petitioned Congress to do something to get rid of the mudflats.

Dredging

1891 “Map of the Anacostia River in the District of Columbia and Maryland. Surveyed under the direction of Lieut. Colonel Peter C. Hains, Corps of Engineers” that outlined initial plans to dredge the Anacostia River’s mudflats. Land that would be reclaimed with dredge spoils are outlined in red.

In 1898, Congress asked the Corps of Engineers for a detailed report on what could be done to “reclaim” the mudflats. The Corps proposed that the Anacostia River should be dredged to create a more commercially viable channel that would enhance the local economy. Linear masonry walls would be built along the river’s sides and the dredged material would be used to build up the marshes behind the walls —drying them out and eliminating the public health dangers they caused, as well as creating useable new land, which the courts determined would belong to the federal government.

In 1901, the U.S. Senate Committee on the District of Columbia created the Senate Park Commission, chaired by architect Daniel H. Burnham. The charge of the Park Commission (better known as the McMillian Commission after the District Committee’s chair, Michigan Senator James McMillan) was to comprehensively plan a new federal park system for the District. Among many other recommendations, the Commission envisioned a great recreational “water park” along the Anacostia River. The Anacostia would be impounded and a three-mile-long reservoir would be formed by the construction of a operable dam built as an extension of Massachusetts Avenue. Inviting “meadows” and sporting fields would surround the lake, and soft edges and gravel beaches would give swimmers and boaters easy access to the water.

Dredging and filling in the marshy wetlands began in 1903 and continued in fits and starts as Congress appropriated funds until World War Two. In June 1915, the dredges discovered two large anchors with many feet of chain attached to them. The anchors were believed to have come from United States Navy gunboat barges burned on the Anacostia River in 1814 during the War of 1812.

The Corps of Engineers abandoned the idea of the Massachusetts Avenue dam and reservoir in 1916 and proposed a new plan for a smaller recreational “lateral basin” on the east side of the Anacostia near the end of East Capitol Street. The basin would be separated from the main river channel by a nearly two mile long “Burnham Barrier” island, created from dredge spoils and bookended by gates to control the flow of water. A concrete lock would allow boats to enter at the south end. This plan was implemented to create what is now Kingman Island and Kingman Lake. However, the new plan didn’t work, as the lake quickly filled up with sediment.

1912 photo of US Army Corps of Engineers vessel dredging the mudflats along the river edge across from the Washington Navy Yard.

1921 photo of US Army Corps of Engineers dredging operation from the banks of Anacostia Park looking towards Washington Gas Light Company’s East Station Site.

1938 photo of seawall construction along the Anacostia River.

1938 photo of seawall construction along the Anacostia River.

Early Development

Kingman Island was conceived as a barrier island to separate the recreational basin from the Anacostia River, but the island itself lacked a purpose. Parts of it were used for garden plots during the depression of the 1930s, and other parts functioned a dump. As early as 1926, the National Aeronautic Association proposed filling in all or part of Kingman Lake to expand Kingman Island so that a new city airport could be built there. Two years later, the piers supporting the Benning Bridge were reconfigured to permit a dredge to pass between them. The reconfiguration was complex, as 92 percent of the city's electrical supply passed through cables carried by Benning Bridge. The new, large dredging ship Benning was used to dredge the upper part of the Anacostia River, and the fill from this operation was used to create the northern half of Kingman Island and two new islands in Kingman Lake, named Island No. 3 and Island No. 4.

In 1934, all parkland in the District formerly managed by the Corps of Engineers was transferred to the National Park Service. In 1946, the last pair of bald eagles on the Anacostia River abandoned their nest on Kingman Island. The bald eagle did not return until transplanted eaglets returned to the river as adults in 2004. The airport project was proposed again in 1947 and 1948, but was not approved.

1922 aerial photograph of progress on dredging the Anacostia River's mudflats to create Kingman Island and Kingman Lake. Note that construction stopped at Benning Rd NE, above which the natural contours of the Anacostia River and mudflats can be seen.

1927 aerial photograph of progress on dredging the Anacostia River's mudflats to create Kingman Island and Kingman Lake. Note that construction stopped at Benning Rd NE and that the converted land had been made into small garden plots.

1929 aerial photograph laying out plans for the continuation of dredging the Anacostia River's mudflats to create the northern half Kingman Island and Kingman Lake at Benning Rd NE.

1931 aerial photograph of the completed dredging of the Anacostia River's mudflats to create Kingman Island and Kingman Lake at Benning Rd NE.

1950S–60s

The city extended East Capitol Street across the Anacostia River and Kingman Island in 1955. DC officials, who had been seeking a site for a large all-purpose sports stadium since the early 1930s, finally won support from the U.S. House of Representatives for a stadium on reclaimed federal land on the western shore of Kingman Lake in 1957. The District of Columbia Stadium (renamed Robert F. Kennedy Stadium in 1968) opened in 1961.

A second concrete span for Benning Bridge was constructed in 1961; the old span now carried eastbound traffic, while the new span carried only westbound traffic. Reclaimed mudflats on the east side of the river (the present-day Kenilworth Park) became a burning landfill until a seven year old boy, Kelvin Mock, was trapped in the flames and died in 1968. Environmental trash and construction materials continued to be dumped. A number of development proposals were made for Kingman Island throughout the 1960s, but none was adopted. The most thoughtful and far-reaching of these was a 1967 plan by nationally-prominent architect Lawrence Halprin, working under the patronage of Lady Bird Johnson and several prominent philanthropists, to build an amusement park on Kingman Island and a cultural center on Heritage, as well to create extensive parkland where the landfill was burning. Yet no funding materialized for these ambitious plans after Richard Nixon took office in 1969.

1954 photo of the East Capitol Street Bridge under construction.

1967 photo of incinerator waste being dumped in Kingman Lake. Credit: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin

National Children’s Bicentennial Island

Conceptual map rendering of National Children’s Island

In 1973, the District created a Bicentennial Commission to manage the local celebration of the 200th anniversary of the American Revolution. DC Mayor Walter Washington, who had been appointed by President Johnson, remained interested in Halprin’s vision. In 1974, the head of the Bicentennial Commission asked Joe Henson, an assistant DC budget director, to evaluate implementing a version of Halprin’s ideas. Henson was a Dunbar High School graduate who had served in intelligence services in the Air Force and the State Department and worked at a high civil service level at the Department of Commerce and HUD.

Joe Henson took on the job of transforming Kingman and Heritage Islands into a fun, educational park for children and families with playgrounds, a children's theater, library and museum, an international mall with exhibits and demonstrations, an animal petting center, a windmill, greenhouse, nature sanctuary, ranger tower, and a carousel. A Native American village, an African village, a frontier village, an 18th Century schooner and paddle boats were also planned for “Heritage” Island, which had previously been unnamed or known as 1776 Island.

The National Park Service gave the city a 25-year permit to proceed. Henson and a handful of others threw themselves into the project. Since there was little cash available, the staff had to find project support from other local and federal government agencies.

A key issue was how visitors would park and access the islands. Henson persuaded the Corps of Engineers to build a wooden pedestrian bridge from the RFK Stadium parking lots as a training exercise, copying the historic Old North Bridge in Concord, Massachusetts, where the first battle of the American Revolution was fought. To attract private donations, a nonprofit organization called National Children’s Island, Inc. was created in early 1976. The bridge was completed and the International Mall was blacktopped, then paved with bricks. 100 cherry trees from the Japanese government were planted around the entrance. Underground electric and plumbing lines were laid and a solar-powered Administration Building and two smaller buildings were built. A yurt designed by national yurt guru Dr. William Coperthwaite was constructed on Heritage Island, and trails were cleared on both islands.

In 1979, the District government announced that it could no longer afford the project, and the buildings, at least one of which had been damaged by fire, would be immediately removed. Despite the setback, the National Children’s Island nonprofit board carried on, continuing to look for private investors to get things going again.

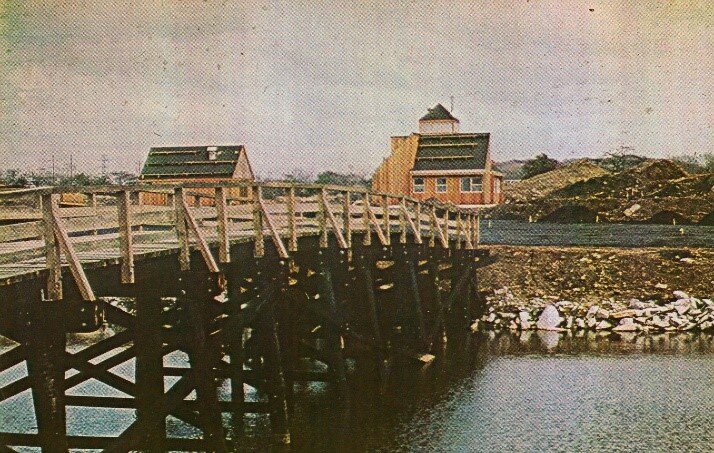

The Kingman + Heritage Island pedestrian footbridge when newly built.

The solar-power Administration Building

Yurt on Heritage Island

1980-2021

The vision of Kingman and Heritage Islands as an children’s amusement park attracted an wealthy Indian-Italian Countess, Bina Sella di Monteluce, whose development company partnered with the nonprofit National Children’s Island, Inc. and offered $150 million to finance the National Children’s Island amusement park. Congress transferred the land from the National Park Service to the District in 1996 to help to facilitate the project, and Mayor Barry and the DC Council then approved a 99-year no-cost lease to the Countess’ company. However, as consciousness about the badly polluted Anacostia River rose in the late 1990s, environmental and community leaders worked to stop the amusement park, and succeeded when the lease was terminated by the DC Financial Control Board for procedural and cost reasons in 1999.

In the early 2000’s, newly elected Mayor and Sierra Club member Anthony Williams and his public-private Anacostia Waterfront Corporation proposed a lower-impact vision for Kingman and Heritage Islands--as a natural area with a state of the art Environmental Education Center. A design competition for the Center was held, and a winning design was selected. However, after Mayor Williams left office and the AWC was abolished by the DC Council in 2007, funding did not materialize and little happened other than a management agreement with Living Classrooms. In July 2016, working with the nonprofit Anacostia Waterfront Trust, the DC Council passed legislation requiring the Director of the DC Department of Energy and Environment to conduct a Planning and Feasibility study to assess the AWC’s vision for the islands. Eighteen months later, Mayor Bowser designated the area the Kingman and Heritage Islands State Conservation Area and asked the DC Council for $4.7 million in capital funds to implement the recommendations of the Planning and Feasibility Study, which it approved. Under the auspices of the DC Department of Energy and Environment, the project is now underway.